By Hunter Allen, Peaks Coaching Group Founder/CEO and Master Coach

originally printed in Road Magazine

We often train for longer races and endurance events lasting

many hours—even days—but it’s rare that we train or do short races like a

prologue or an uphill time trial. These essential competitions seem to be in

short supply throughout the good ol’ USA, and I wish we had more opportunities

to prove our mettle in these unique events, because they demand something

different from a road race or a criterium. The aspects of your fitness that

these incredibly intense short fights demand are special. Riders that excel in

them are even called specialists. Someone with incredible handling skills to

navigate sharp turns at light speed, along with an unnatural desire to push

himself to the white-foam-producing, lung-heaving state of suffering that so

many of us avoid at all costs might have the ability to become such a

specialist. But what about the rest of us? Those of us who have trained for

100-mile road races, for 40-mile crits, and for the dreaded district

40-kilometer time trial—how should we prepare, strategize, and pace ourselves

in these other-worldly sufferfests?

One of the best ways to learn how to excel in any discipline

is mimicry. Watch the best and do exactly what they do in the hope of

duplicating their winning sets of skills and effort. Let’s examine a couple of

these intense efforts by a few winners and see what we can learn. Before we

examine those gut-busters, however, we need to discuss the proper warm-up for a

short time trial. In general, the longer a time trial or effort, the less

intense the warm-up you want to do. For a 24-hour race, some light stretching

is enough. For a 40-kilometer TT, you’ll want at least 30 to 45 minutes of

fairly vigorous efforts including intervals done at your FTP. For an event only

3 to 4 minutes (up to 15 minutes) long, you’ll want to really push it in your

warm-up with intense intervals over your threshold and get in at least 30-45

minutes of warming up. The first goal of these warm-ups is to increase the

blood flow to the working muscles so that they literally begin to heat up and

loosen, giving you a faster response to your internal drive. The second goal is

to get over the fight or flight response by getting your heart pumping near its

maximum rate, which will assure the rest of your mind and body that you aren’t

being chased by a bear and that you’re just at a bike race. By doing multiple

efforts, ramping your heart rate to your threshold or even higher to your max,

you’ll ensure that you get over this fight or flight response.

Here’s my recommended warm-up for your short game:

- 15 minutes at endurance pace (Level 2: 56-75% of FTP) 90-100rpm

- 3 x 1-minute fast pedaling intervals at 110 rpm, with 1 minute at 80 rpm between each. Focus on the speed, not the watts.

- 5 minutes at tempo pace (Level 3: 76-90% of FTP), 90-100rpm.

- 2 ramps, each 5 minutes long and ramping up to your FTP (Level 4: 100% of FTP) in minute 4 to 5. Ride easy for 5 minutes between each at endurance pace (Level 2: 56-75% of FTP).

- Finish warm-up with 15-20 more minutes at endurance pace (Level 2: 56-75% of FTP), then roll to the start line.

One important thing you should always take into

consideration in short efforts is your anaerobic capacity. This energy system

works at its maximum when you are fully rested, so if your warm-up is too intense,

you risk using up a good bit of this system and reducing your wattage in the

first few minutes of the effort. With this in mind, stay away from doing

all-out type efforts when warming up for a short time trial. In a longer time

trial (greater than 15 minutes), you should be able to do some all-out efforts

without hurting your chances.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s examine a hard

prologue race. Riding over your FTP will be the norm for very short events, so

the numbers you read about and see in your own training and racing will be

higher than your traditional, ride-at-threshold-by-the-book time trial. In the

screenshot below, you’ll see that this rider started out strong and pushed over

his FTP by 36%, averaging 572 watts in the first 45 seconds. He then settled in

to a rhythm for the next two minutes, averaging 546 watts (still 30% over his

FTP). At 2 minutes and 45 seconds into the effort, his anaerobic capacity was

clearly exhausted, and his power started dropping off to the finish. In the final

57 seconds, he averaged 483 watts (15% over FTP) as he struggled to the finish

line in a winning time of 3:42. One thing is clear from just reading the

numbers: a winner of short prologues must have an incredible anaerobic capacity

and the ability to suffer to the deepest, darkest of dark places.

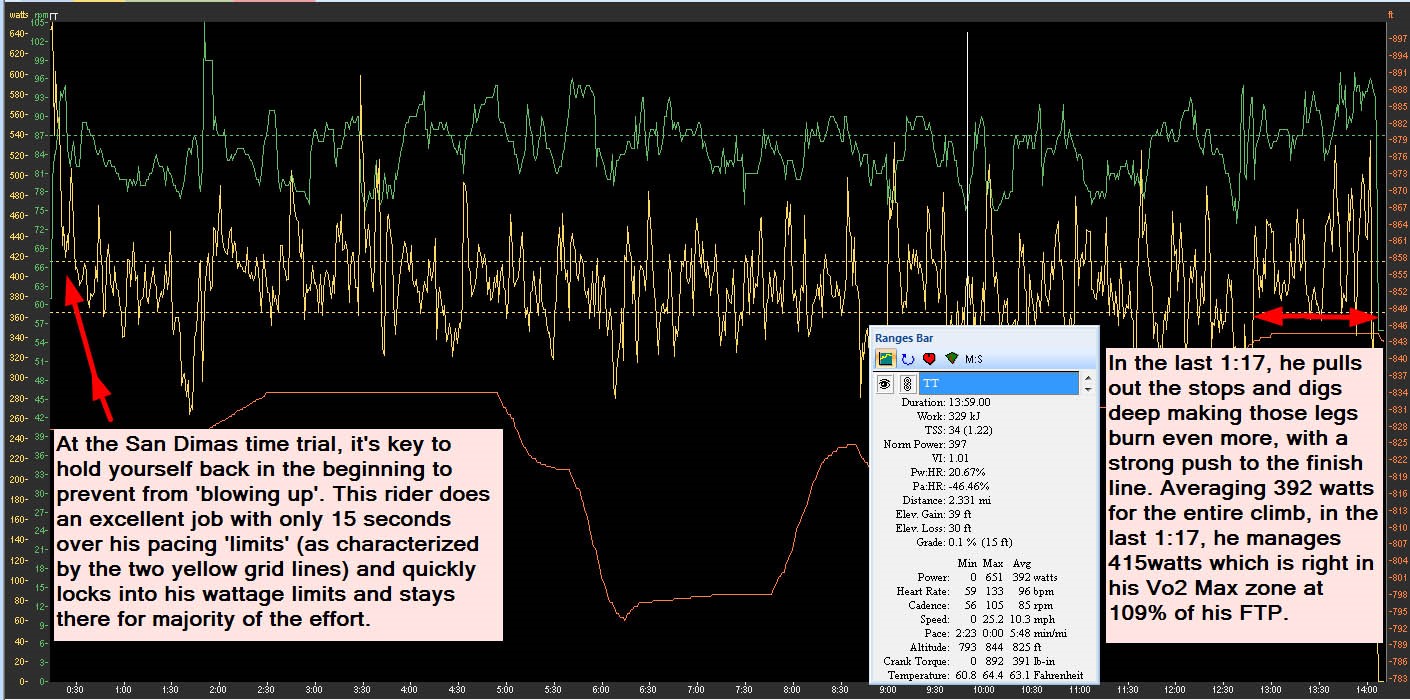

San Dimas is an early spring race many riders do on the west

coast that includes a hill climb time trial for its first stage. It’s a tough

little stage, not too long and not too steep, and as a hill climb time trial it

is by nature a sufferfest. The screenshot below is from a rider who placed in

the top ten and did a good job of pacing himself through the time trial. In a

time trial longer than 10 minutes, pacing becomes more a part of the strategy,

and it’s important that you don’t start too hard. If you start too hard, you’ll

blow up halfway through and have nothing left for the final half. On the other

hand, if you hold back too much, you’ll under-perform and your slower time will

reflect that suboptimal performance. The rider in the chart below knows this

very well, and I gave him an upper and lower limit to his wattage for the time

trial. This can be a useful tool in a short TT (and in a long one), especially

if there are undulations to the course. I told him to keep his watts over 365

but under 420 as much as he could, which would give him some goals to shoot for

when he got tired. In the first 15 seconds he got himself up to speed,

averaging 484 watts, but then he settled into his limits and averaged 391 watts

for the next 12 minutes. Keeping himself within these limits allowed him to

ride right on the “edge” with an extra push for the last minute. In that last

minute he was able to dig deep and push to 109% of his FTP (415 watts), giving

him precious speed that kept him in the top ten for the stage. The power file

sports the classic double peak profile that indicates a personal best effort

has been reached, and this is something I look for in time trials and in

training when an athlete needs to do his best.

The training for a prologue or shorter time trial must

consist of four main components. The first is plenty of threshold training in

order to put out the highest threshold power you hold. This means plenty of 2 x

20, 4 x 15, and 6 x 10 minute intervals done between 100-105% of your FTP. The

higher your FTP, the faster you’ll go. Period.

Secondly, you’ll need to address your VO2Max and anaerobic

capacity in order to be prepared for the prologues and short hard bursts of

efforts above your FTP during the time trial itself. I suggest doing 7 x 3, 8 x

2, and 10 x 1 minutes on a regular basis (do 1 VO2Max and 1 AC per week) in the

final four weeks before your event. The 3-minute VO2Max intervals should be at

115% or greater of your FTP, and you’ll have to push even harder in the 1- to

2-minute efforts, striving for 135% or greater.

The third component of this training is to come up with and

master your pacing strategy. By carefully analyzing the event itself, you’ll be

able to figure how many watts you should hold for the event. From that initial

number you can dig deeper into the course and apply specific tactics along the

way, like pedaling harder on the steepest sections. Pacing is an art, and it

takes practice. I highly recommend doing some practice time trials, using your

power meter for accurate effort measurement, and downloading your data later

for analysis. The key things you’re looking for are (1) sustaining power with

an increase towards the end of the effort, (2) starting too hard (evidence of

this would be a premature decline in power before the finish), and (3) the ability

to push harder on the steeper/headwind sections.

The fourth and final component you need to master is the

easiest one. Rest. When doing a very short time trial, you need to make sure

your glycogen stores are packed full! The shorter the time trial, the more

important your anaerobic capacity is for success. If you’re coming into a

stand-alone race on the weekend, you’re best off just resting and riding very

easy the entire week before. If you’re doing a stage race and the first stage

is short, I suggest tapering more than normal, so that the first time trial

stage serves as your “blow-out” or tune-up effort to open up the legs for the

rest of the race. Resist the urge to go hard the day before, or the entire week

before, as your anaerobic capacity can be used up easily and quickly.

Short time trials have special demands that can be trained

for, and the races themselves are great tests of truth. This special discipline

within cycling has specific keys for success, and if you’re getting ready for a

big event this spring that contains a short time trial, make sure you adhere to

the suggestions in this article for a top performance. Remember, all the best

physical training will get you nowhere without the proper mental attitude, so

when preparing for your event, stay focused, prepare to suffer, and dig deeper

than ever before. And win!