By PCG Elite/Master Coach Karen Mackin

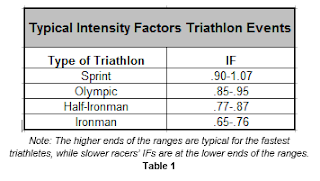

Choosing the correct overall intensity for the bike split of

your race is probably the most important thing you can do to have a successful

triathlon. If you have a power meter, choosing the correct intensity is as easy

as looking up a number in a table (see table 1) and either displaying Intensity

Factor (IF) or Normalized Power (NP) on your bike computer during the race.

Since IF = NP divided by Functional Threshold Power (FTP), you can calculate a

target NP by simply multiplying your target IF by FTP. Once you’ve decided on

your target intensity, wouldn’t you like to ride as fast as you can at that

intensity? If so, read on:

Riding the fastest split possible for a given intensity

factor is all about managing variations on that intensity. Some small

variations in intensity during the bike split may be necessary (i.e. to take

advantage of terrain and or wind conditions), however, these changes should be

relatively small. Your power meter is the ultimate tool to learn how to manage

these variations. In this article I will first provide you with a little

background, and illustrate why lower variability allows you to go faster, then

I will provide you practical advice on determining how well you are managing

variations, and finally, give some examples of how to keep these variations to

a minimum.

We all know that Normalized Power represents an estimate of

the power you would have maintained “if” your ride had been perfectly constant.

However, it is important to know that AVERAGE power, not normalized power,

determines how fast you cover the course. Variability Index (VI) is a measure

of how variable the ride is, and is computed as the ratio of your normalized

power over average power (VI=NP/AP).

Consider the scenario of an ironman triathlete with a Functional

Threshold Power of 280 watts, who wants to have a good run split. He chooses an overall Intensity Factor (IF)

of .70 to target. Since IF = NP/FTP,

that means he would target 196 watts as his normalized power. Now, let’s

compare what happens when he is able to manage variations during his ride with

a VI of 1.05, as opposed to if he rides with a higher VI of 1.15.

|

Case 1

A Lower VI of 1.05

Since VI = NP/AP, then AP = NP/VI

AP = 196/1.05 = 187

|

Case 2

A higher VI

of 1.15

AP = NP/VI

AP =

196/1.15 = 170

|

You can see that the average power is higher when the

variability is lower. Essentially, this means he is able to go faster given the

same target normalized power, or intensity factor, than he would have if he

rode with a lot of variability. As I stated earlier, a certain amount of

variability may be necessary to take advantage of terrain. This is due to the fact

that it is not optimal to put out exactly the same power going up a hill as it

is going down because the additional wind resistance on the downhill will only

give you marginal increase in speed compared to going uphill. So, your VI

should reflect the terrain of the course. For flat courses, target VI’s should

be between 1.00 and 1.03. For courses with hills, good VI goals would be

between 1.04 and 1.07.

So, how well do you manage your variability? In

TrainingPeaks you can look at your variability index after you download your

workout. I recommend that all of my athletes do a test ride on a course that is

similar to their event (or ideally on the course) and see how they fare. Now

that most bike computers/watches will enable you to display both your average

power and your normalized power you can see how you are doing during your ride.

If your goal is to keep your VI to 1.05 or less, then you just need to make

sure that your AP and NP are within 5% of each other and it is a simple matter

to compute what that wattage difference is.

Two common reasons for excessive variability are 1)

non-optimal gearing for hilly courses, and 2) power spikes. In order to

minimize your variability, it is very important that you are not forced into

riding at too high a wattage on a hill because your cadence otherwise would

become too low. Ideally, even on the steepest of climbs, you should be able to

maintain at least 70 rpm while climbing. If you are unable to do this, you’d

best head out to your local bike shop and get a new gear setup. AND, once you

have those gears, don’t be afraid to use them! The second reason, power spikes,

occur with excessive surging coming out of corners, or at the bottom and top of

hills where the gradient changes, trying to pass someone, or getting out of the

saddle to power over a short climb. These variations should be minimized! Focus

on every one of those little things that can cause micro bursts in your power,

become very aware when you do them, review your power files after your rides

and make a concerted effort to avoid those spikes.

With a little awareness and practice, you will be able to

get to the target VI that is appropriate for your race. And when you do, you

will maximize your speed for your chosen goal intensity.